|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

From San Antonio (Oeste) intermittently to Bariloche An interrupted start

Obverse and reverse of the medal presumably struck to commemorate the start of works in 1910.

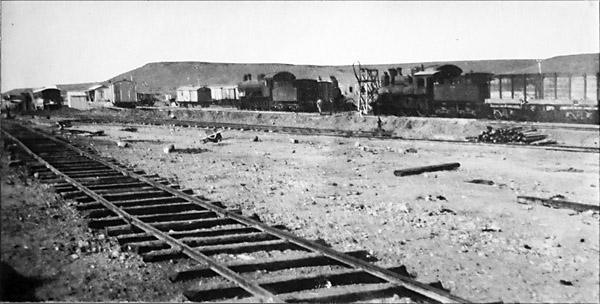

The plans were approved in August 1909, under law 5559, see Appendix 1 for the text, and work began on the first 110 km. to Valcheta. Construction of all three Patagonian lines was under the overall direction of Ingeniero D. Guido Jacobacci who took personal command of this particular route. A photo of a narrow gauge 0-4-0T arriving on a lorry for use in the construction is displayed in Chapter 13. Most materials arrived by sea at San Antonio where a new muelle was built - soon to be surrounded by railway stores and workshops and the first temporary station. A railway hospital was built and houses for the engineers and administrators. In 1910 President Figueroa Alcorta paid a visit to inaugurate the new line. See Appendix 20 for his speech. The state railways bought rails for their existing lines and new construction by open tendering. The awarding of contracts was by presidential decree. For the year 1909 the contract was placed with Ramsay, Bellamy y Cía, representing the United States Steel Products Export Company, to supply rails in various amounts to various places including 6262 tons delivered to San Antonio for $32.30 sealed gold per ton. The section of rail was not specified. See Appendix 22 for the text. A pair of Maffeis bring a train into the loop at the railhead early in the life of the line. The front loco is number 337.

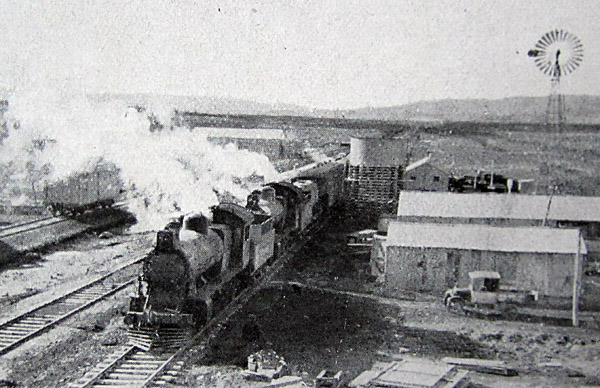

In December 1909 the second section had been approved, at a similar cost of around 19,000 gold pesos per km. Km. 217 (west of Ministro Ramos Mexía) seems to have been reached by September 1911. By 1915 the line had been opened another 151km. to Maquinchao, but war conditions slowed work thereafter and although rails stretched as far as Ing. Jacobacci in early 1917 no further progress was made. From March 1916 the line became the responsibility of the FC del Estado, up to that time having been constructed directly by the Ministry of Public Works. Aguada Cecilia station, during the construction of the route. The locos would appear to be a Maffei Pacific and one of the five Baldwin 4-4-0s.

Work began again in 1922 and by the end of 1923 the operating line was 281 miles long. Construction was then started eastwards, back towards Viedma, with a view to linking up with the main Argentine network via a 200m bridge across the Río Negro to Patagones. Viedma was reached by 1925 but even then the line remained isolated from most of the Argentinian system, for it was only in 1936 that the river was bridged to join the FCE line to the Buenos Aires Great Southern network and create a through route to the Federal Capital. Progress westward was slower, and Pilcaniyeu was not reached until not until1926. After further delay a bigger effort was then made to finish the line; opening finally to San Carlos de Bariloche in 1934.

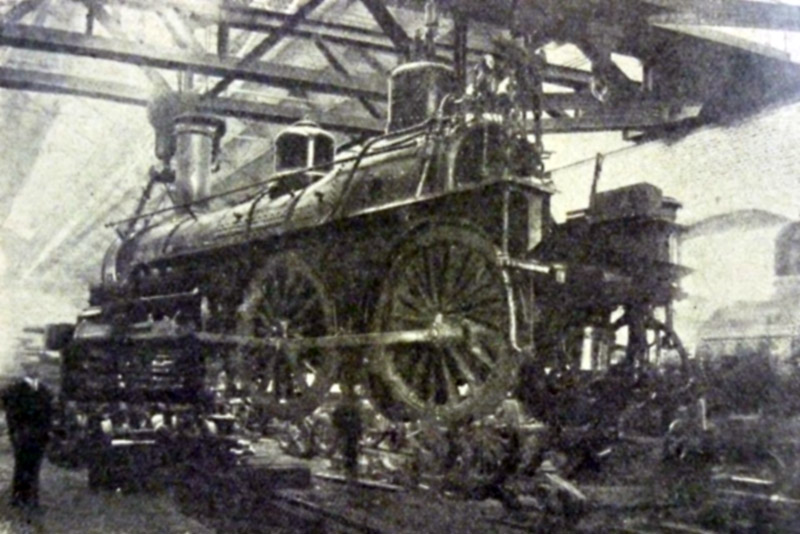

A passenger train at the Pilcaniyeu railhead in the 1920s, as shown in the FCE 1930 timetable book. The locos are both Maffei pacifics, built new for the line around 1911. It is worth noting that there had been plans to extend the broad gauge further, to Llao-Llao, south to El Bolsón, and even across the Andes to Osorno in Chile. Work on the first of these, and on a grand hotel at Llao-Llao, was summarily halted by Dr. Pérez, the new Administrator-General, on the occasion of his visit in 1925 (4). However, the public park at Llao-Llao, near Puerto Pañuelo, contains a path looking very much like a railway alignment, over masonry bridges and through rock cuttings (7). This may be part of the incomplete FCE route. San Antonio and its works However, when construction work started, there were no workshop facilities available here, nor at Comodoro Rivadavia and Puerto Deseado. New material was generally supplied in knocked-down form in units that could be unloaded onto a beach and assembled on site in the open with minimal plant. However, the 55 new steel wagons supplied by the Leeds Forge Company appear to have arrived in kit form, which could only be assembled at the Tolosa (near La Plata) workshops of the FC Sud, asis evident from a presidential decree (see Appendix 22) Second hand material came from the FC Andino (Government owned) on its disposal to the private sector and required overhaul, repair and re-branding. As this was beyond what could be done on site, the work was undertaken at the workshops of the Bahía Blanca Noroeste railway. Surprisingly these poor quality views taken in the works have been found by the enthusiastic local railway historian Héctor Guerreiro. The first two views are taken in the locomotive erecting shops while the third is taken in the joiners' shop.

Interestingly the coach has been re-branded 'PATAGONICOS', while there is a view of the sole short coach at Comodoro Rivadavia showing it still carrying its 'ANDINO' branding.

Reports from the south indicated that some of the patagonicos tank wagons could not be completed and the tanks had as a consequence been mounted on plataforma wagons. This group of four such assemblies was taken in 1915 on a Valcheta water train.

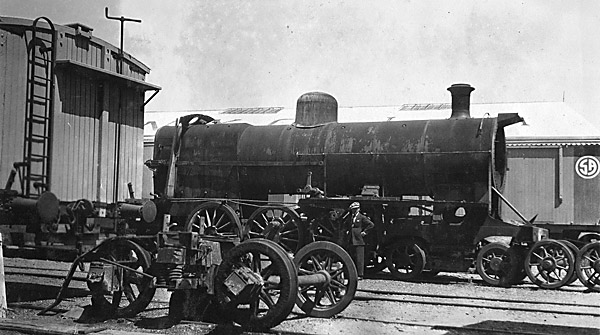

A Maffei pacific is seen dismantled for overhaul at San Antonio works. Also of interest is the SA logo on the van in the background. Each of the Patagonian broad gauge lines had its own symbol made up from the letters SA, CR or PD in a circle as here.

The railway's starting point and port facilities were on the west side of the bay and given the vast tidal range at this location (approx. 9 m at springs) they obviously dried out at low tide. It is interesting to note that Ing. Jacobacci was talking in the 1920s of a proposed 47km branch around the east side of the bay to a proposed new deep water facility (1). This was never built. When the line to Viedma was commenced it branched off the original line to the west of the town before rounding the north of the bay. This left San Antonio on a short branch. The railway initially built muelles for the unloading of materials. Offices for the management, a hospital, houses for the senior staff, and a 'barrio' of workers' accommodation all grew up. The works were first established to erect the new locos, but grew to maintain all the stock on the line, which for its first twenty or more years was isolated from the rest of Argentina's broad gauge network. Most tasks could be dealt with, in a wagon shop, paintshop, boilermakers' shop, and having even a wheel lathe for loco driving wheels. There was also a large 'vías y obras' area for the permanent way and civil engineering teams. Power for the workshops came initially from a 30hp Blackstone engine though in 2000 the site still had a Ruston steam portable engine lying derelict. Later of course electric power was increasingly used, from the town's own generating plant. A catastrophe came in November 1943 when a large part of the works burnt down. However the new manager, Don Bernardo Aimar, shifted machines to local warehouses and soon managed to resume work on an improvised basis. However, from 1950 onwards the role of the works began to decline (). The narrow gauge Esquel line established its own facilities at El Maitén. Then the broad gauge steam locos were replaced by diesels, maintained in Bahía Blanca. Wooden wagons and coaches were succeeded by steel and aluminium-bodied vehicles. In 1961 the government proposed to shut the workshops, together with a number of other national railway facilities. Eventually a solution was found in the transfer of the works to a separate cooperative, COMSAL, which would subcontract work on wagons from the FC General Roca. Additional jobs were taken on in the repair of equipment from the fishing fleet and for the YPF state petroleum business. Activity since then has been erratic though there is still a little work to be undertaken for the new owners of the railway, SEFEPA, later known at Tren Patagónico. Main features of the route A comprehensive list of locations on the line with their facilities is in an appendix page. Click here to move to that page.

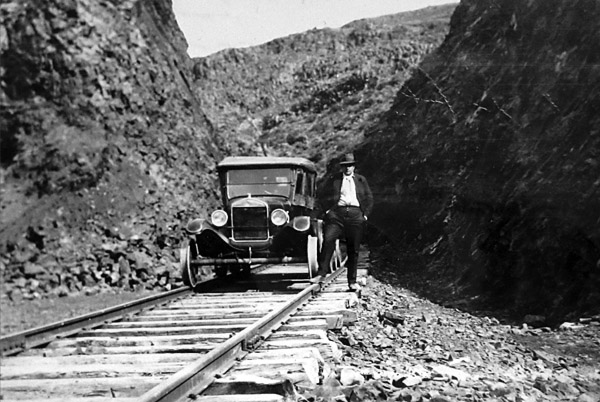

Rögind in his history of the FCS covers the development of tourism in the area thanks to the joint efforts of the FCS and the FCE. The relevant part of his chapter is available in an appendix page. Water supply for locomotives was always a problem at the San Antonio end of the line, being brought down in tanks from the reliable stream at Valcheta. This problem must have contributed to the early decision to go diesel in 1953. An inspection car on rails in the Neneo Ruca gorge possibly in the 1920s.

Empalme Km 648 (from Viedma) where the economic gauge La Trochita peels away towards Esquel. The very British style junction signal was taken out of use in the mid 1990s but nevertheless the remaining arm still sports its out of use cross.

A view of the derelict station building at Km. 648. A 75cm gauge van stands in the left background.

One of the smaller wayside stations on the approach to Bariloche.

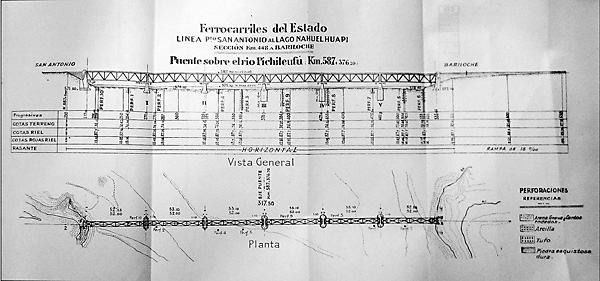

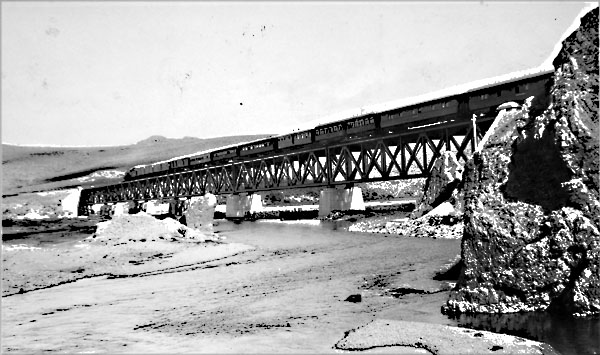

The Pichileufü bridge about 30 miles before Bariloche. The coach over the right hand pier is an FC Sud type R7 sleeping car, one of 18 built in 1922/23 on six-wheel bogies (6)

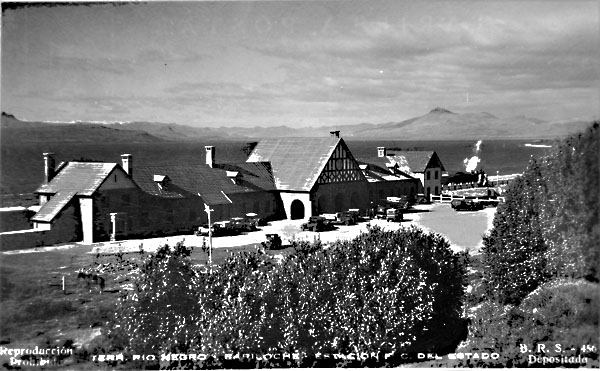

A postcard of the station at San Carlos de Bariloche probably shortly after the opening of the line in 1934 (6).

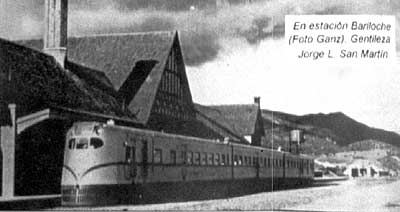

One of the TB class three-car Ganz diesel units sits in Bariloche station in about 1938.

The booking hall as seen in June 2011.

A view (2000) of Bariloche engine shed, just west of the station and the true end of the line.

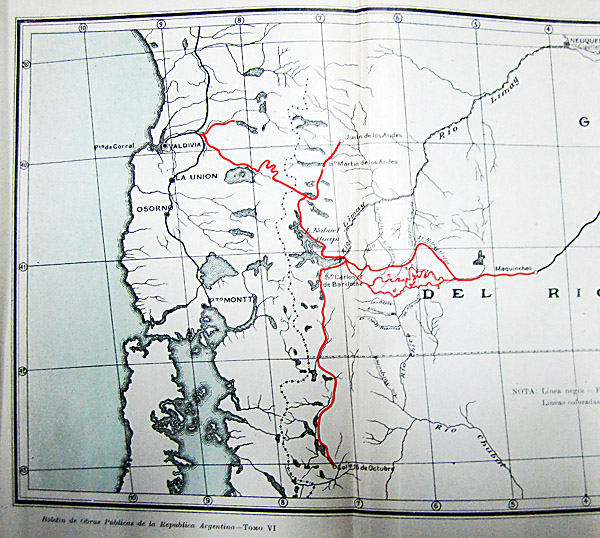

There had been long-standing proposals for the railway to be extended beyond Bariloche. The American geologist Bayley Willis had been engaged in 1912 to consider not only the railway's route west but also the prospects for industrial development in the area. Whilst many of his proposals, including a new induxtrial city at the east end of Lago Nahuel Huapi, did not come to fruition, after the first world war the renewed work on the railway included some excavations further west with a view to opening the railway as far as the big hotel at Llao-llao. This was cut short after a change of railway management in 1924, as can be followed in Señor Perez' report in an appendix page to Chapter 7. This 1912 map shows alternative routes for the approach from the east to Bariloche, and then a proposed route north-westward towards Valdivia, as well as a branch up to San Martín de los Andes. and another southward to Trevelin.

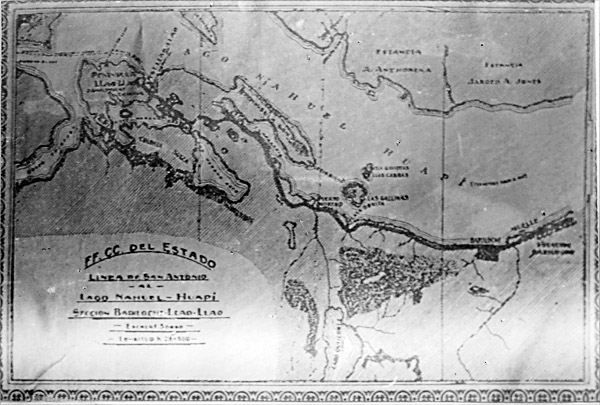

The intended short extension beyond Bariloche to the hotel on the peninsula at Llau-Llau is shown as a thick black line on this map. Bariloche station is the black rectangle towards the right side. It will be noted that a siding down to a muelle on the lake is shown just east of the station. It is not yet known whether this was ever constructed.

Operating

Like most railways in Argentina the FCE used British style semaphore signals. In the smaller stations these would be worked from an open ground frame. The latter were definitely not of British style. The picture far left illustrates a four lever frame and the extreme movement of the levers - almost down to ground level - can be seen. The weights part-way down the levers allow for wire length compensation in varying temperatures and also make it easier to pull a stiff wire. The first movement of the lever initially raises the weight a little rather than jerking the whole length of wire; by the time the wire actually gives, the lever is moving well; and the weight's movement back down the lever puts extra tension on the wire.

For many years the line was worked using miniature electric train staff instruments, assembled under licence in Argentina. This one is on display in the main booking hall at Bariloche.

Traffic

The most interesting figure in the above table is the last one. Clearly at this stage the railway's biggest task was the transport of new material to the railhead in preparation for its extension further west. Overall tonnages for the line including its narrow gauge branches from 1916 to 1941 are in the following table:

More detailed figures for passenger and cargo in the early 1940s were published in the FCEs's history of Argentinean railways (3). They are reproduced below: Whilst the passenger figures are not far from those in the table above, the commercial traffic figures for 1941 and 1942 are now not far below the totals in the above table, showing that the railway's own materials were now far less important as one would expect.

Timetables The working timetable (el itinerario) for 1946 has been studied, and also the late 1955 public passenger timetable which is available on an appendix page. In 1946 there was a through passenger train all the way from Patagones to Bariloche three times a week, one more than in 1934, with an additional through mixed train once a week. There were paths in the timetable for a goods train three times a week and for a goods, parcels and personnel train also three times a week. There was also a goods and water train five times a week as far as Valcheta. Given that the Ganz diesel 'Trenes Bariloche' would have been running at that time, it seems surprising that the shortest journey times were still 22hrs. The 1955 document gives a good deal less information of course, but there appears to be only the 'Tronador' through train twice a week and an additional passenger train once a week. Héctor Guerreiro has very kindly provided a diagram of the lines radiating from Bahía Blanca on which was indicated the line limits as far as Bariloche. These have been extracted and are shown below. Bahía Blanca FC General Roca Only two tickets from the FCGR era are known about. The first is an unusual one, dating from the occasion of a national election. The second is for the member of a group travelling from Buenos Aires all the way to Bariloche. SEFEPA, later to become Tren Patagonico A pause at an intermediate station, Pilcaniyeu. There are two car transporters between the luggage van and the engine. The parcels barrow is of typical Argentine design and is called a siriaca.

Recent news References: 16-11-16 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Chapter 4

The FCE broad gauge network

Main pages

Bariloche line rolling stock •

Com. Rivadavia line extra photos •

Pto. Deseado line extra photos •

Pto. Deseado line extra photos 2 •

Appendices

2 Chronology of Patagonian railway proposals •

3 Bariloche line route itinerary •

4 Com. Rivadavia route itinerary •

5 Pto. Deseado route itinerary •

7 Com. Rivadavia line loco list •

8 Pto. Deseado line loco list •

15 FCP working timetable instructions 1960 •

16 Report on construction 1912 A •

17 Report on construction 1912 B •

21 President Alcorta address •

23 Purchase of wagons decree •

25 Early Patagonian proposals •

26 Progress to Bariloche 1926 •

28 Restructuring report 1953 •