|

Operating the FC de Chiloé

August 25th, 1936,

Plaza Hotel,

Ancud, Chile.

"The train left this morning at 9:00; such a funny little affair, About as narrow a gauge as you can imagine; a tiny little wood-burning engine; baggage car and 1st and second class coaches, the seats running along the sides. It's 80 km - about 50 mi. - to Ancud, and it takes 5-1/2 hours! For one thing the train ambles along about 15 mi. an hour; at least the landscape doesn't whizz by and you can see everything along the way. Then it stops quite often, at each little cluster of houses, sometimes for only a minute, and several times to take on wood and water - then everyone gets out to walk up and down. At some of the stations women were selling the very smallest apples I've ever seen - and probably as sour as the ones on Maillen, near Puerto Montt. Everyone comes down to see the train, the men in their best and brightest ponchos. At noon we stopped for luncheon at a little restaurant out in the middle of nowhere..."

Margaret

The above extract, from a young American woman's letter home to her mother, gives a flavour of operations on the Chiloé railway mid-way through its life (15).

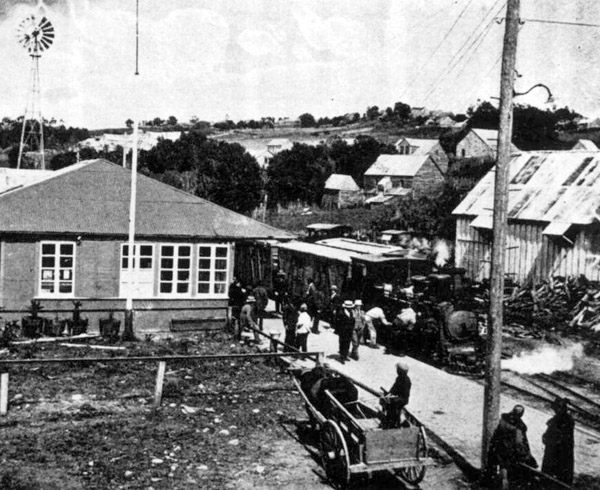

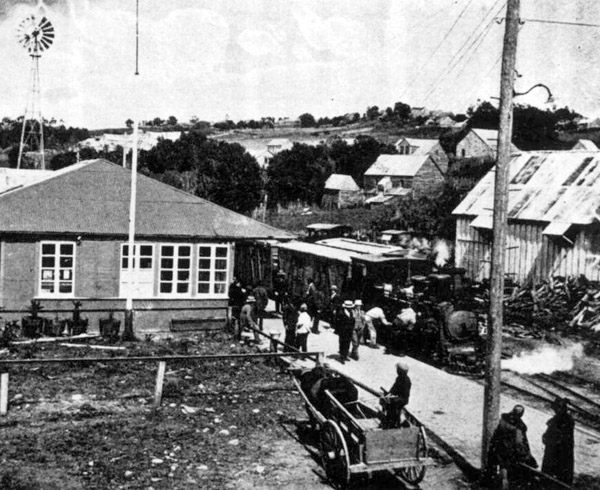

An A class 0-6-2T has just arrived at Ancud station. The two front vehicles appear to be goods vans but the number of people about suggests that there may be a passenger vehicle behind. In the background two other locos stand outside the loco shed which is piled high with timber presumably for fire lighting.

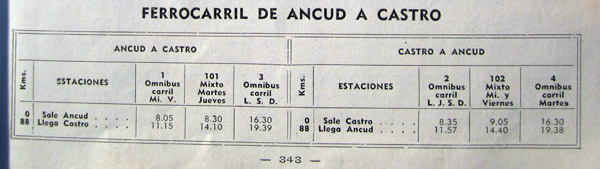

Timetables

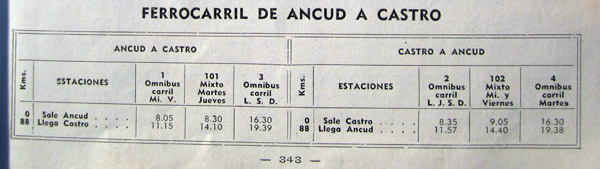

The tables below show the railway's passenger timetables in 1912, in 1924 and then in 1939. It will be apparent that there were only three passenger trains a week iin 1912 and 1924 but by 1939 the introduction of 'auto-carrils' had made it possible to have a daily service. Interestingly, in 1912 the trains ran through in four and three quarter hours or so, whereas by 1924 the custom of having an early lunchbreak at Puntra had stretched the overall time to five and a quarter or five and a half hours. By 1939 the steam trains were taking five hours but the 'autocarrils' managed it in three.

Boldrini suggests that for the first year or two the trains actually picked up and set down anywhere along the line (1).

Itinerario tren de pasajeros 1912

Ferrocarril de Chiloe

|

ANCUD a CASTRO

|

Martes, Jueves, Sabados

Tues., Thurs., Sats.

|

Kms.

|

lleg. = arrive

sale = depart

|

0

|

Ancud sale

|

8.55 am

|

8

|

Pupelde lleg.

|

9.15

|

19

|

Coquiao lleg.

|

9.43

|

36

|

Puntra lleg.

|

10.28

|

52

|

Butalcura lleg.

|

11.09

|

67

|

Mocopulli lleg.

|

12.42 pm

|

|

Pid-Pid lleg.

|

13.14

|

88

|

Castro lleg.

|

13.40

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CASTRO a ANCUD

|

Martes, Miercoles, Viernes

Mon., Wed., Fri.

|

Kms.

|

|

0

|

Castro sale

|

8.30 am

|

|

Pid Pid lleg.

|

9.30

|

21

|

Mocopulli lleg.

|

10.00

|

36

|

Butalcura lleg.

|

10.40

|

52

|

Puntra lleg.

|

11.43

|

69

|

Coquiao lleg.

|

12.28 pm

|

80

|

Pupelde lleg.

|

12.57

|

88

|

Ancud lleg.

|

13.19

|

|

|

|

Source: From 'La Cruz del Sur' 5th Oct. 1912, as quoted in (2) and (3).

|

Itinerario 1924

Ferrocarril de Chiloe

|

ANCUD a CASTRO

|

OMNB.

Dom. y Mierc.

Sun. & Wed.

1

sale depart

|

MIXTO

Viernes

Friday

101

saledep.

|

Kms.

|

|

0

|

Ancud

|

9.00

|

9.00

|

8

|

Pupelde

|

|

9.27

|

19

|

Coquiao

|

10.00

|

10.08

|

36

|

Puntra

|

11.22

|

11.30

|

52

|

Butalcura

|

12.15

|

12.24

|

67

|

Mocopulli

|

13.05

|

13.18

|

75

|

Piruquina

|

13.32

|

13.49

|

83

|

Llau-Llau

|

13.59

|

|

88

|

Castro

|

14.15

|

14.30

|

|

|

|

|

CASTRO a ANCUD

|

OMNB.

Lunes y Jueves

Mon. & Thurs.

2

sale depart

|

MIXTO

Sabado

Sat.

102

saledep.

|

Kms.

|

|

0

|

Castro

|

9.00

|

9.00

|

5

|

Llau-Llau

|

9.19

|

|

13

|

Piruquina

|

9.49

|

9.53

|

21

|

Mocopulli

|

10.17

|

10.22

|

36

|

Butalcura

|

11.06

|

11.12

|

52

|

Puntra

|

12.23

|

12.30

|

69

|

Coquiao

|

13.18

|

13.27

|

80

|

Pupelde

|

|

14.03

|

88

|

Ancud

|

14.15

|

14.30

|

Source: a 1924 shipping gazetteer in Centro Cultural library, Castro (4).

|

Itinerario Invierno 1939

|

ANCUD a CASTRO

Cuadro 34

|

101

Mixto

Martes

|

|

1

Autocarril

Miercoles, Jueves

|

|

3

Autocarril

Lunes, Viernes, Samedi, Domingo

|

Kms.

|

|

Llega

|

Sale

|

Llega

|

Sale

|

Llega

|

Sale

|

|

ANCUD

|

....

|

8.00

|

...

|

8.25

|

....

|

14.30

|

2,0

|

Kiómetro 2

|

(f)

|

8.05

|

(f)

|

8.29

|

(f)

|

14.34

|

7,9

|

Pupelde

|

8.20

|

8.22

|

8.41

|

8.42

|

14.46

|

14.47

|

18,9

|

Coquiao

|

8.59

|

9.04

|

9.04

|

9.05

|

15.10

|

15.11

|

25,0

|

Kilómetro 25

|

(f)

|

9.19

|

(f)

|

9.16

|

(f)

|

15.22

|

31,0

|

Kilómetro 31

|

(f)

|

9.39

|

(f)

|

9.29

|

(f)

|

15.35

|

36,2

|

Puntra

|

9.55

|

10.00

|

9.38

|

9.40

|

15.44

|

15.45

|

52,1

|

Butalcura

|

10.47

|

10.52

|

10.10

|

10.11

|

16.15

|

16.16

|

60,0

|

Kilómetro 60

|

11.16

|

11.17

|

10.25

|

10.26

|

16.30

|

16.31

|

67,5

|

Mocopulli

|

11.39

|

11.47

|

10.39

|

10.40

|

16.44

|

16.45

|

75,6

|

Piruquina

|

12.07

|

12.11

|

10.55

|

10.56

|

17.00

|

17.01

|

77,4

|

Pid-Pid

|

12.16

|

12.17

|

10.59

|

11.00

|

17.04

|

17.05

|

83,0

|

Llau-Llau

|

12.43

|

12.46

|

11.10

|

11.11

|

17.15

|

17.16

|

88,3

|

CASTRO

|

13.07

|

|

11.25

|

....

|

17.30

|

....

|

|

|

|

CASTRO a ANCUD

Cuadro 34-A

|

102

Mixto

Viernes

|

2

Autocarril

Lunes, Samedi, Domingo

|

4

Autocarril

Martes, Miercoles, Jueves

|

Kms.

|

|

Llega

|

Sale

|

Llega

|

Sale

|

Llega

|

Sale

|

88,3

|

CASTRO

|

...

|

8.00

|

....

|

9.25

|

....

|

14.30

|

83,0

|

Llau-Llau

|

8.20

|

8.23

|

9.49

|

9.50

|

14.44

|

14.45

|

77,4

|

Pid-Pid

|

8.45

|

8.46

|

9.59

|

10.00

|

15.55 (sic)

|

14.56

|

75,6

|

Piruquina

|

8.51

|

8.55

|

10.03

|

10.04

|

14.59

|

15.00

|

67,5

|

Mocopulli

|

9.21

|

9.25

|

10.19

|

10.20

|

15.15

|

15.16

|

60,0

|

Kilómetro 60

|

9.46

|

9.47

|

10.33

|

10.34

|

15.29

|

15.30

|

52,1

|

Butalcura

|

10.10

|

10.15

|

10.48

|

10.49

|

15.44

|

15.45

|

36,2

|

Puntra

|

11.02

|

11.07

|

11.19

|

11.21

|

16.15

|

16.17

|

31,0

|

Kilómetro 31

|

(f)

|

11.23

|

(f)

|

11.32

|

(f)

|

16.28

|

25,0

|

Kilómetro 25

|

(f)

|

11.42

|

(f)

|

11.43

|

16.39

|

16.40

|

18,9

|

Coquiao

|

12.03

|

12.07

|

11.55

|

11.56

|

16.51

|

16.52

|

7,9

|

Pupelde

|

12.42

|

12.44

|

12.18

|

12.19

|

17.13

|

17.14

|

2,0

|

Kilómetro 2

|

(f)

|

12.59

|

(f)

|

12.59

|

(f)

|

17.26

|

....

|

ANCUD

|

13.04

|

....

|

12.35

|

....

|

17.30

|

|

(f) = Detención facultativa

|

|

|

A summary timetable for 1940 shows the same pattern as 1939, though the autocarrils had been retimed slightly. Autocarril 1 had been shifted by 5 minutes, departing Ancud at 08.30, whilst autocarril 3 had been moved two hours, departing Ancud at 16.30 instead of 14.30. In the return direction autocarril 2 had been brought forward to depart Castro at 08.30, whilst autocarril 4 had been delayed by almost two hours, departing Castro at 16.20. In each case the journey durations and days of operation remained the same as in 1939.

A passenger timetable for 1951 is displayed below. There would appear to be mixed trains in each direction twice a week, and bus-carrils each way five times a week. The steam trains are now taking over five and a half hours whilst the bus-carrils manage the journey in three hours ten minutes or three hours twenty.

In the early days there may have been separate freights, however in later years there was clearly only sufficient traffic to justify the mixed trains.

The branch to Lechagua

This appears to have been constructed in the expectation that Lechagua would become a port in its own right for the export of timber. However, there were problems right from the start. The branch took off from the main line in Ancud up the steeply graded Calle José Andrade. This then mean that steam locos were working extremely hard up a town street, with the consequence that cinders caused fires.

Management decision-making is as yet unclear, but in 1919 the operation of this branch line was sub-let to Señor José Manuel Mulet for nine years at an annual rent of $600 (Chilean currency) payable weekly in advance.

Bridge reconstruction

It is clear that the bridges were causing concern almost from the day of completion. The timber trestles were seen as inadequate and dangerous, the more so because the damp Chiloé climate would lead to rapid deterioration. A number of bridges were rebuilt in mass or reinforced concrete during the 1920s, whilst culverts were replaced by tubes. In an unrelated incident, the river bridge at Puntra, presumably a concrete replacement for the original, was completely destroyed by the river in spate during 1935. The line was blocked for 83 days until a replacement could be provided.

Tickets

So far only one ticket has come to light, a third class example from Butalcura to Coquiao, in the care of the family of Señor Felipe Ojeda of Ancud, an inspector on the railway in its latter years, and who very kindly permitted it to be copied.

Personnel

An article in La Cruz del Sur during 1912 named the principal members of staff of the new railway (4A). Whilst this list is clearly not complete it does give some indication of the line's organisation:

Primera dotación de personal

del servicio de FFCC Ancud-Castro

Initial staff list

|

Personal superior

|

|

Ingeniero Jefe y Administrador

|

Don José A. Koch

|

Contador Jefe

|

Don Ignacio Bravo

|

Secretario de Administración

|

Don Alvaro del Villar

|

Jefes de Estaciones de primera clase

|

|

Ancud

|

Don Luis Swart

|

Mocopulli

|

Don Nicanor García

|

Castro

|

Don Angel Araya

|

Maestranza

|

|

Ingeniero Mecánico

|

Don Max Lenarhd

|

Tracción

|

|

Conductor

|

Don Ramón Alvarado

|

Mecanico

|

Don Teléforo Castillo

|

Maquinista

|

Don Lucas Siguel

|

Maquinista

|

Don José R. Garrido

|

|

|

Traffic

A set of 1915 figures (5) shows that timber made up almost 50% of the goods carried; coal and firewood totalled nearly 27%. Potatoes were the next largest item at 6.2%. The timber traffic was always a mainstay; there were six sawmills along theline.

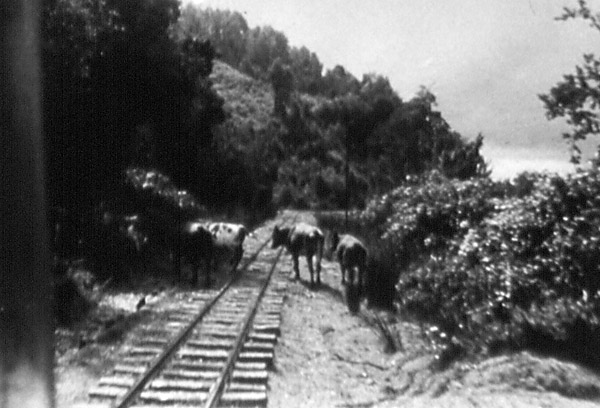

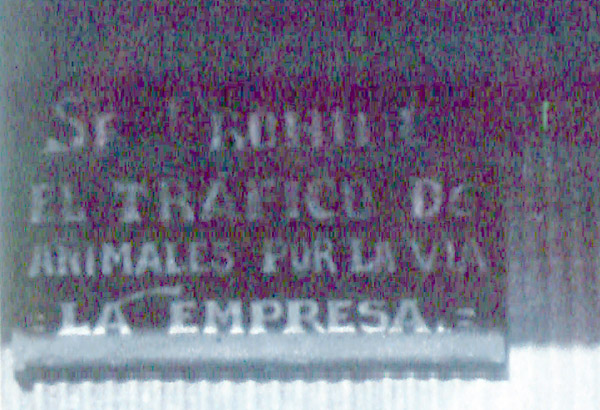

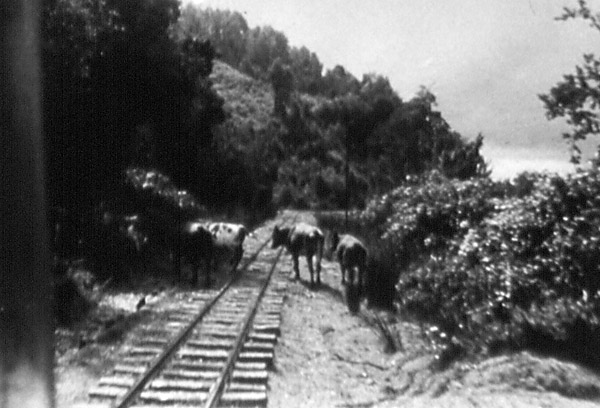

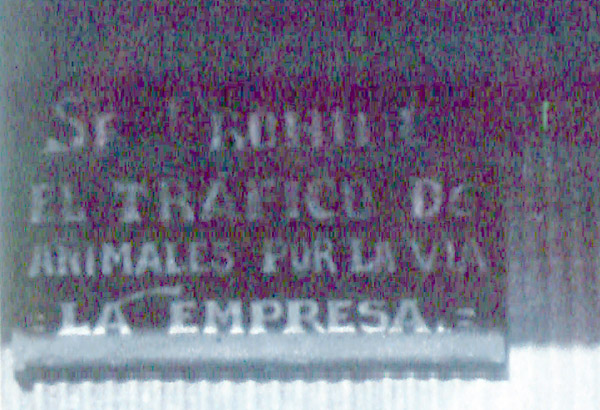

Trafico de animales!

A 1949 visitor (6) commented on the cattle wandering the track (above) whilst the station at Castro (below) displayed a clear notice warning against such usage. The similar notice at Butalcura (below that) was still just visible in 2001!

Problems soon arise

From an early date it was obvious that the railway was not justifying the initial optimism. It was too slow; it only served the two main towns and the deserted central area rather than the highly populated east coast; the gradients were too steep for the locos; and there were no weighbridges so overloading of wagons led to damage and accidents. As early as August 1912 the FCE were noting that traffic levels were not as high as expected, and locos intended for Chiloé were being diverted elsewhere (7). In 1913 income was $(m/n) 45.465 whilst expenses were $145.850. The year’s passenger total was 16.000 and the freight traffic 4.400 tonnes (8).

Traffic did build up during the 1920s and into the ’30s. The table below shows the traffic figures for 1939:

Ancud -Castro traffic figures 1939 (9)

|

Stations

|

Passenger tickets sold

|

Goods loaded

Tonnes

|

Goods unloaded

Tonnes

|

Ancud

|

17.854

|

551

|

5.503

|

Pupelde

|

231

|

20

|

22

|

Coquiao

|

664

|

1.730

|

|

Puntra

|

487

|

3.509

|

|

Butalcura

|

263

|

5.304

|

|

Mocopulli

|

898

|

1.956

|

|

Piruquina

|

670

|

3.194

|

25

|

Pid-Pid

|

|

|

|

Llao-Llao

|

|

|

61

|

Castro

|

5522

|

223

|

10.894

|

Total

|

26.589

|

16487

|

16.505

|

The passenger figures are fairly respectable and would have demanded rather more than the initial three trains per week, for remember that each train was limited to two coaches and a van. The figures in fact represent about 500 passengers per week. The major part of the freight carried was loaded at intermediate stations for carriage to either Ancud or, increasingly, Castro. Much of it would have been timber for shipment to the mainland. On average it represents about 330 tonnes per week. Since freight trains are unlikely to have been much heavier than the passenger trains 50 tonnes was probably about the maximum cargo per train. At this stage the railway was operating about seven round trips per week for passengers and possibly about three per week for goods traffic.

The figures continued to rise a little further into the war years, probably because road transport would have been suffering from a shortage of fuel. However, by the 1950s things were getting more serious. Whilst passenger totals held up respectably for some time, three quarters of the goods traffic had gone by 1955 (10). I doubt whether the FC del Estado had ever really bothered themselves much about the line, and now the neglect was beginning to show. When the main road from Ancud to Castro was improved bus or 'micro' services started up, doing the journey in a quarter of the time and at half the cost. By 1958 the passenger figures were falling significantly.

Accidents

Photographs exist of two accidents to steam-hauled trains. One of these, probably in the 1930s, is illustrated below. Another, at an unknown date, also resulted in the locomotive turning over. This second incident in volved 0-6-2T no 5039, and may have been near Coquiao. A final accident, when a bus-carril hit a fallen tree near Mocopulli in January of 1960, resulted in four fatalities.

Closure

The first suggestion of closure came up in that year, 1958, to a chorus of protest, but the figures were difficult to argue against (11):

Pasage

Passenger receipts

|

$ 6.277.522

|

Equipage

Luggage receipts

|

$255,347

|

Carga

Goods receipts

|

$6,071,402

|

Otras entradas

Other receipts

|

$797,688

|

Total

|

$13,401,951

|

Gastos

Expenditure

|

$119,328,648

|

In other words, the line was only covering 11% of its costs.

|

It was announced that the last train would run on 3rd March 1959. This date came and went whilst politicians argued and attempts to arrange a takeover by the army or by a cooperative failed. Another definitive closure date was announced - 1st January 1960. The line was struggling by this time. It still had three steam locos and a couple of railcars, but a serious blow was the fatal accident near Mocopulli in that January when a 'bus-carril hit a fallen tree killing four people and injuring seven(12).

However, the final coup de grace came on 21st May 1960 in the form of the Valdivia earthquake. This damaged bridges, demolished buildings, created rock and soil falls in the cutting sides, and flooded substantial sections of the route when sea level rose.

The photo shows the flooding in Castro at the time of the earthquake. It is obvious from the piled up rails that some dismantling had already taken place (13). The building on the right was the loco shed.

The late Wilfred Simms (14) suggests that official permission to remove the track was given in 1961 and that dismantling took place during 1961-2.

References:

1 El Tren de Chiloé. 1986. Gustavo Boldrini P. Centro de Folklore Magisterio Ancud. Page 41, quoting La Cruz del Sur, Ancud, 25 September 1912.

2 Ibid. Anexo 5.

3 Mito, Historia y Leyendas del Tren Chilote. 1996. Carlos Mendez Notari.

4 Guia Maritima de Chile. 1924 edition. pub. Ricardo Swett O., Valparaiso.

4A La Cruz del Sur, 18 September 1912, as quoted in Boldrini. Op. cit.

5 Mito, Historia y Leyendas del Tren Chilote. Op. cit., Page 22.

6 Captions in Brattstrom collection, library of Centro Cultural, Castro.

7 El Tren de Chiloé. Op. cit., page 41, quoting La Cruz del Sur, Ancud, 21 July 1912.

8 Los Ferrocarriles de Chile. 4th edition 1916. Marín Vicuña, Santiago.

9 Ferrocarriles del Estado 56a. Memoria (correspondiente al año 1939). Santiago.

10 Ferrocarriles del Estado, Datos de los servicios (correspondiente al año 1955). Santiago.

11 El Tren de Chiloé. Op. cit., page 48.

12 El Tren de Chiloé. Op. cit. page 48, quoting La Cruz del Sur, Ancud, 16 January 1960.

13 Photo of 1960 floods from Arquitecturas del Sur. 1988. Booklet pub. by University of Biobio.

14 The Railways of Chile, Volume 5 - Southern Chile. 2002. Wilfred Simms.

15 Extract from a letter written by Margaret (Peggy) Bird to her mother back in the USA. Reproduced by kind permission of her son, Henry Bird.

29-10-11

|

|