|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

Getting the coal to the coast Background Whilst there were deposits on the Argentinian side of the border they suffered from the difficulty of not being able to get the product out easily without crossing Chilean territory. This had also been a difficulty in the development of agriculture further north, in for example the Río Baker area. I suspect this was the reason why it was not until the 1940s that exploitation started in the Río Turbio district of Santa Cruz province. Coal from Río Turbio Sentinel steam wagons A small coal washing plant was also brought into use in 1950, another stage in the transformation of an experimental facility into a practical production plant. The surviving Sentinel lorry is shown below, as it was at the Río Turbio mining museum. The other photos show the Sentinel name cast into the undertype engine housing and the wheel hubs respectively.

The Sentinel wagon preserved at Río Turbio has recently been overhauled (2016) by Cromwell Engineering in Buenos Aires. The photo below shows it during that work. Its present location is not known.

Proposed routes The mine owners, at that stage Argentina's national petroleum company (Yacimientos Petroliferos Fiscales or YPF), cast around for an easy way to build the line. The solution was to use some of the 75cm. gauge equipment and stock that was still lying at Puerto Madryn, unused since the abandonment of the ambitious 1922 plans. 300km of 17.36 kg/m rail were available there, with another 90 km of similar material at Rio Grande for the Ministry of Marine's abortive Tolhuin railway. Construction work Ing. Atilio Cappa was the engineer, an employee of the Ministry of Public Works. In a departure from traditional practice motor lorries were used to transport material beyond the railheads. By May 1951 all but two miles were complete, with the finishing touches made in September, after the worst of the winter.

What is possibly a posed photograph as there is no sign of a works train with sleepers and rails at the end of the track laid.

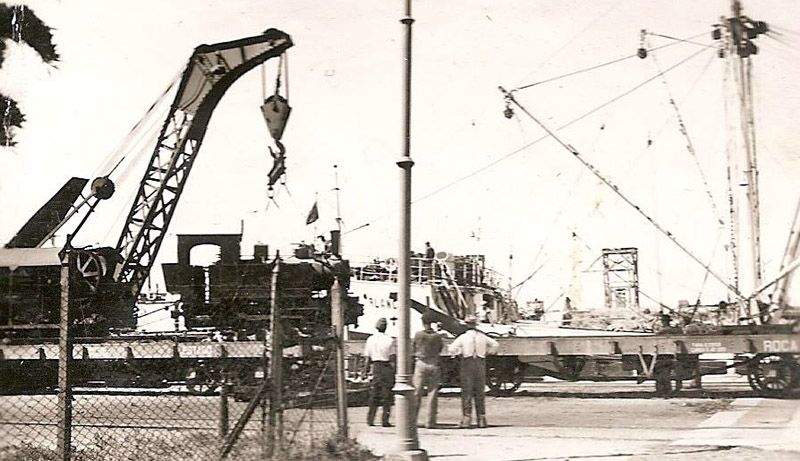

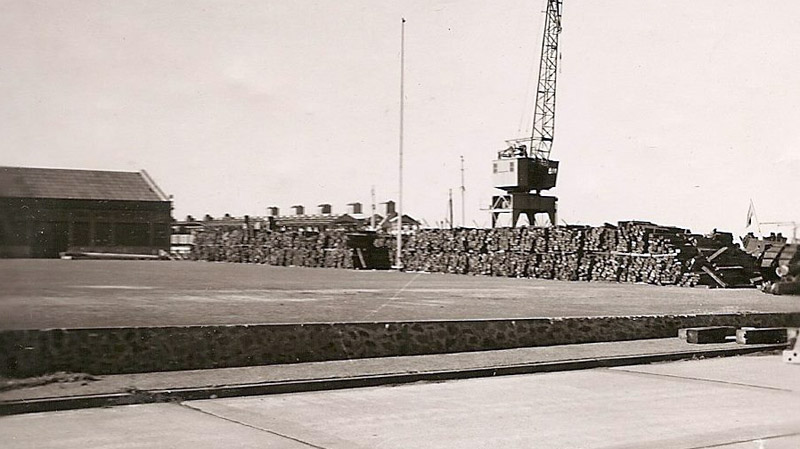

The formation has been completed by Vialidad Nacional, and now the railway squads from the Central Norte section of the new FCN Belgrano move in to lay the track. First the sleepers with pre-drilled holes for the rail spikes are dropped in position as precisely as possible by eye, a pinch-bar is used to slide it about if it is not quite right. Then four spikes are laid ready for the next step. The rails are carried from the wagon on the shoulders of the squad, dropped in place, loosely jointed to the rails already laid, and a start made to spiking them down. The spikes would not be driven home completely at this stage as it may be necessary to make minor adjustments to the positioning of the sleeper, before completing the driving home. While the track is nowhere near finished yet, it is good enough for the works train to use to bring up more materials. We thank Héctor Guerreiro for finding this view. The Bahía Blanca North Western workshops played a major role in getting stock ready for the South. It re-gauged a number of wagons which had started life on the metre gauge Central of Chubut, and which had been lying unused in Puerto Madryn since the early 1930s. It also re-furbished the Ministry of Marine four wheel wagons, which formed the bulk of the initial rolling stock. It is remembered that these were treated differently from the routine work – all work was carried out in the open, and no drawings were prepared to show what work was required, nor any record or diagrams prepared for the completed work. This view shows one of the 0-6-0Ts being loaded at the docks at Bahía Blanca. It had been taken to the Bahía Blanca North Western Workshops for a major overhaul before being shipped south. It is being lifted off an Estado flat wagon by the local broad gauge breakdown crane. The wagon next to it has already been re-branded into Roca after the nationalization of the FC Sud.

Incredibly there is a view of the 6-wheel brake van being loaded here as well. (10)

The third picture show a great many sleepers stacked ready for despatch. Broad gauge sleepers from depots all over the country had been taken to Bahía Blanca to be cut into two halves, before being shipped south. (9)

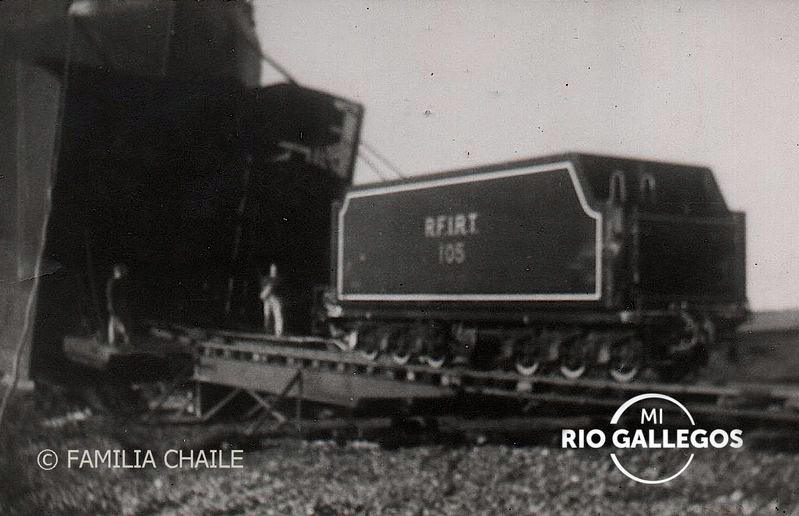

The two views show what was involved in bringing the Mitsubishi locos to the line. There were no dock facilities in Río Gallegos at the time. Here the landing craft has been beached, and men are busy at work preparing a temporary line to run the loco from the landing craft to the railway. It is likely that the landing craft was loaded at Bahía Blanca, the most southerly port which could deal with lifting the locomotive on to the ship, thus involving the shortest possible voyage. The source of this view is Facebook, with authorship as noted. (11a) [2480]

In this view the temporary line has been completed and the tender of № 105 is being drawn up the beach. It was taken from the same source. (11b) [2471]

These two black and white photos are of the first days of the line. The one above is supposed to be of the very first train to run right through - hauled by a Henschel 2-8-2 and made up mostly of four-wheeled wagons. The picture below was taken on the opening day, when the Minister of industry and commerce, Don José Constantino Barra, cut the tape to allow the first official train through in November 1951.

The opening A few wagon axlebox covers survive showing the original initials of the RFIEP. Observant readers will notice that this one was actually fastened on upside-down, as evidenced by the oil build up at the top as well as the dandelion top right!

The new line was laid with 17kg./m. rail from the stocks at Puerto Madryn (soon replaced with 24 and 32 kg./m.), and ten locomotives and a large number of wagons and cars were also shipped south from Puerto Madryn to operate the new link. The next pages describe the stock in detail. Until a new muelle was opened at Río Gallegos in August 1952 all materials brought in and coal sent out had to use the beach. In fact the CSM, after first using the steamer Bahía Aguirre of the Comando de Transportes Navales ( a fleet auxiliary service supplying Patagonian establishments), purchased two tank landing craft from the US Navy. The principal customer for the coal was the new San Nicolás power station in Buenos Aires province. There were others, and during the first few years the Perón government applied pressure to encourage the use of Río Turbio coal by for example the frigorifico in Pto. Deseado, but it was difficult to find willing private customers and throughout the life of the mine the vast majority of the coal has gone to government users. As the railway gradually ceased to be the bottleneck limiting production, so output rose. A new coal washery opened in 1958 lifted throughput to 250 tonnes per hour. New ships were purchased, and at the same time coal moved out from under the shadow of the petroleum industry through the creation of Yacimientos Carboniferos Fiscales to take over the responsibilities of CSM including the mine and railway.

The route in detail

The role played by areal photography in identifying previously unknown Roman army camps in the UK is well known, as is its connection with the Nazca lines in Peru. We discovered that Google Earth can be used in the same way, particularly in the arid parts of Patagonia, where vegetation does not grow rapidly over the surface and obstruct marks on it. Between El Turbio and Glencross stations we found what appeared to be a new alignment, extending about 2 km, in which the line was moved away from the río Turbio and straightened. There is no reference to this work being carried out in any of the published accounts of the railway. It is not very likely that we would have spotted the divergence of the two lines had we been on the footplate, and there wouldn’t have been much chance either had we been walking the line at this point. There is a Facebook group Mi Río Gallegos which deals with the past of the town and its dependant countryside; an enquiry about the possible diversion of the line was made; a reply was quickly received, confirming that there had been a diversion, and explaining that it had been done as the original line was subject flooding from the adjacent river. This is a good example of the tools which are available to researchers nowadays, making distant investigations far more feasible and economic. (12) Screen shot from Google Earth of the diversion near Glencross. The yellow is the bed of the río Turbio; the black splodges are clouds. El Turbio is off the view to the left and Glencross to the right. [2507]

References: 23-3-2021 |

||||||||||||||||

Main pages

Appendices

Chapter 9

Coal railways including the RFIRT