|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

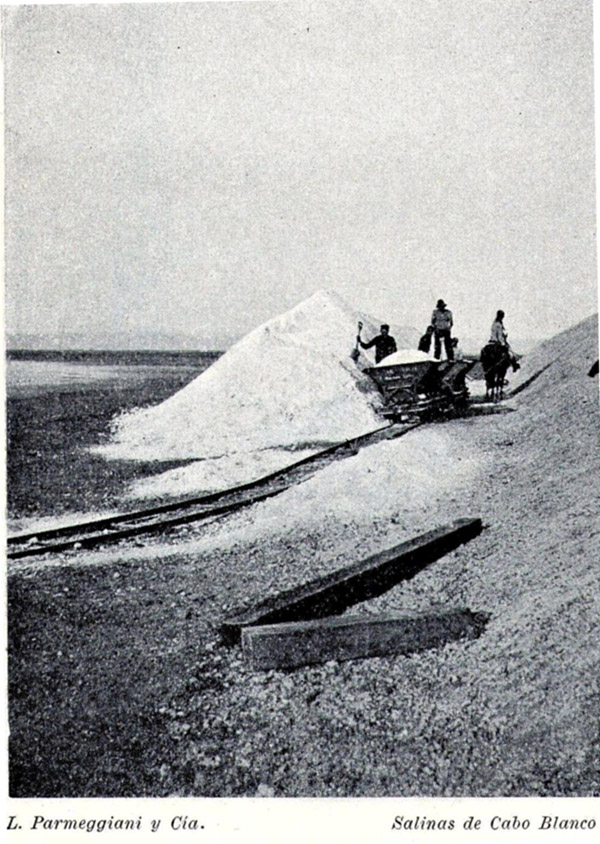

Taking salt to the sea 2, the railway at Cabo Blanco north of Puerto Deseado Approximately 50 miles north of Puerto Deseado there is a large salina just inland from the Cabo Blanco headland. In pre-frigorifico days salt was much valued in the area for the preservation of meat and skins of sheep and of seals. Thus it was no surprise when in 1899 Don Miguel Martínez applied for a concession for two areas within the salina (1). Surveying work commenced in 1901 with a view to extracting the surface deposits, though in fact the deeper reserves have been estimated at between 15 and 40 million tons. Extraction began in 1902, by L. Parmiggiani et Cia. under the title of the Compañía de las Grandes Salinas de Cabo Blanco, and in time a sizable community grew up, with lodging houses for workers post office, court house, police station and school. It seems to have been a lawless place, with reports in La Prensa and La Nacion of murders and assaults. A narrow gauge railway was soon constructed from the salina to the bay south of Cabo Blanco, a distance of 5.6km, opening in 1905. The gauge was 60cm. Unlike the Peninsula Valdes line this salina lies at sea level, however the railway still had to climb 30m or so to the level of the surrounding plateau or meseta before dropping to sea level again close the coast. It will be no surprise that the gradient appears to have been steeper for empty trains than for those proceeding loaded to the coast. Such an arrangement is common practice when a railway's traffic is mostly one way and when the topography allows. The RFIRT is similarly laid out within Patagonia. Using Google Earth's measurement tools suggests that the Cabo Blanco line might well have climbed at roughly 1 in 125 out of the salina, and dropped at 1 in 40 to the coast. This photo, from Fransiscvo Scardin's 1906 volume La argentina y el Trabajo, shows skip wagons of salt on the esdge of the salina, having been pulled up from the workings by the horse or mule beyond them.

The website quoted above includes references to press reports of ships loading up to 3000 tonnes each, so the annual output will at times have been very substantial. A substantial report on the history of the salt industry at Cabo Blanco is available in Spanish within the Faro Cabo Blanco website (2), whilst an English translation is in one of our appendix pages by kind permission of the authors. The line was reportedly initially worked by a Krauss 0-4-0T locomotive of 1890 (3), hauling wagons carrying the sacks of salt. However, the original source of this information is unknown, as is the original home of the loco, for 1890 is twelve years before this railway was built. The steam loco lying derelict at Cabo Blanco in later years was an 0-6-0T and probably an Orenstein & Koppel.

These two photographs (2) were taken in 1920-21 by Señor who was the lighthouse keeper at the time. Clearly there was a re-equipping of the line and the internal combustion engine loco possibly was part of the process, though we have no evidence about the fate of the partly collapsed pier. Skip wagon bodies are being manhandled from a lighter, and in the lower photo a pile of the uprights from skip wagons and a stack of decauville style pressed steel sleepers can be seen. A stack of rails lies behind the men in the lower picture, resting on the remains of the pier. A number of bales of wool stand on the left, awaiting embarkation once the lighter has been emptied.

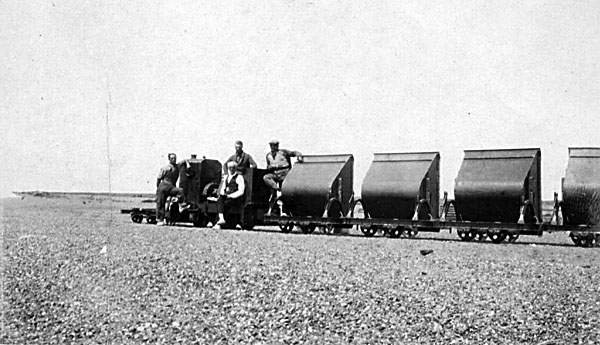

The next two photos show that the railway eventually gained a small internal-combustion engined loco after the First World War. Señor Carlos Santos, who kindly supplied the photos, stated that these pictures were taken in 1921. That must mean that the machine is petrol-engined rather than diesel, and the consensus is that it was an early O&K, possibly of class M.

The upper photo shows a line of skips in the salina, headed by the petrol tractor and with a braked flat wagon ahead of that.The other picture shows a similar line of skips, looking very new indeed, as does the loco. The shingle beneath suggests that this was taken at the beach rather than at the salt flats. It is possible that the picture was taken at the same time as the first two above, when new skips and materials had just arrived. Though if that was the case the means of unloading such a heavy object as this tractor remains uncertain. The skips were presumably for use within the workings, whilst for the longer journey to the beach flat wagons would have been more suitable for carrying the sacks of salt.

The salt extraction apparently ceased around 1930, owing to the difficulties of getting workers to the isolated site and the costs of sending the salt north by sea. The railway and warehouses are reported to have been maintained until 1941 but gradually decaying thereafter. The lighthouse construction Locomotives The undated photos below shows the remains of the steam loco. It may well be that this was abandoned after the arrival of the i.c. tractor pictured above. At some unknown date after the Second World War a scrap merchant cleared this and maybe other remnants of the railway. The group of young men were members of a visiting football team, whilst the young boy in the other picture was Daniel Espíndola, the son of the Cabo Blanco lighthouse keeper.

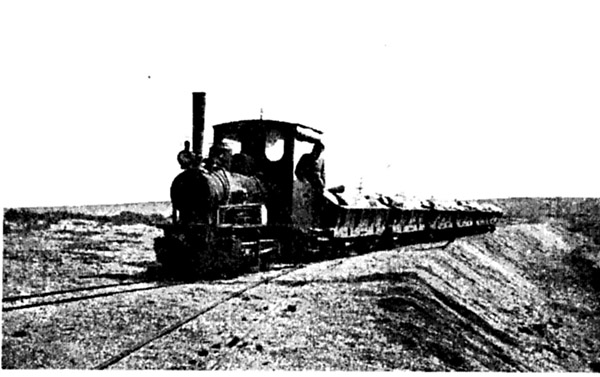

As itnessed by two 1921 dated photos above, there was also a small internal-combustion engined tractor, probably just in the later years. The concensus seems to be that this is an early Montania/O&K with a petrol engine and probably of class M. Wagons However, a photo in Carlos Santos' book on Cabo Blanco (4) shows the stem loco hauling larger bogie wagons loaded with sacks of salt. Nothing further is known of these as yet. The photo discovered by Señor Carlos Santos of Pto. Deseado, and its source identified by Señor Humberto Brumatti of Gualeguaychú, shows the 0-6-0T but on a train bogie wagons approaching the terminus beside the sea. ()

The trackbed as it is now A view out across the salina from the loading point. The dark spots in the distance are the stumps of posts from a platform that was built out over the salt.

Looking west along a low ambankment towards the terminus with the edge of the salina to the right.

The sole remnants of a Koppel skip wagon. It is no surprise that in such salt-laden atmosphere everything but the thicker riveted seams has rusted away completely.

The following photos show the other end of the route, at the coast. The first looks west along the old alignment which at this point has dropped down from the low hills in the distance onto the wide flat isthmus of sand which joins the rocky headland of Cabo Blanco to the mainland. Again a low and now rounded embankment can be seen.

The next photo looks the other way, east towards the railway's terminus below the rocky headland. The darker items are the rusty remains of dozens of steel sleepers from the track panels of which this line was constructed.

Looking down from the lighthouse we can see the wide sheltered bay to the south, and the remaning two buildings of the old 'pueblo' - the post office and the telegraph linesman's house. The railway came from the west, where the low hills in the distance run off the right hand side of the picture, and headed straight for the buildings. There is now no sign of the old muelle on the beach by the post office. The curving alignment further right is the modern road to the lighthouse.

One surprising survivor is a skip wagon chassis, now preserved and repainted up on the platform by the lighthouse. It, like the rest of the railway's equipment, would seem to have been bought off the shelf from the Koppel agency in Buenos Aires. This was found recently at a nearby estancia, further confirming the suggestion that after the closure equipment was borrowed for use throughout the neighbourhood.

References: 1-11-11 |

|||||||||||||||

Chapter 12

Salt carrying railways